Let me start with a confession: Last week, I spent $47 on a hamburger. Not because it contained gold flakes or was blessed by Gordon Ramsay’s tears, but because the menu said it was “artisanally crafted” and came with “hand-foraged” mushrooms. Did it taste better than the $15 burger from the joint down the street? My brain certainly thought so. My credit card statement, however, remains unconvinced.

This brings us to one of psychology’s most delicious ironies: the price-placebo effect, where your brain essentially cons itself into believing that expensive equals exquisite. It’s like a magic trick you perform on yourself, except the only thing disappearing is your money.

The Wine That Launched a Thousand Brain Scans

Picture this: You’re a sommelier at a swanky restaurant. Customer A orders a $30 bottle of Pinot Noir. Customer B, trying to impress their date, orders the $150 bottle. Here’s where it gets interesting—what if you secretly served them both the same $30 wine?

Before you report me to the wine police, consider this: researchers at Caltech and Stanford actually did something remarkably similar. They gave people the exact same wine but told them it cost different amounts. The results? Mind-blowing, wallet-emptying, and slightly embarrassing for humanity.

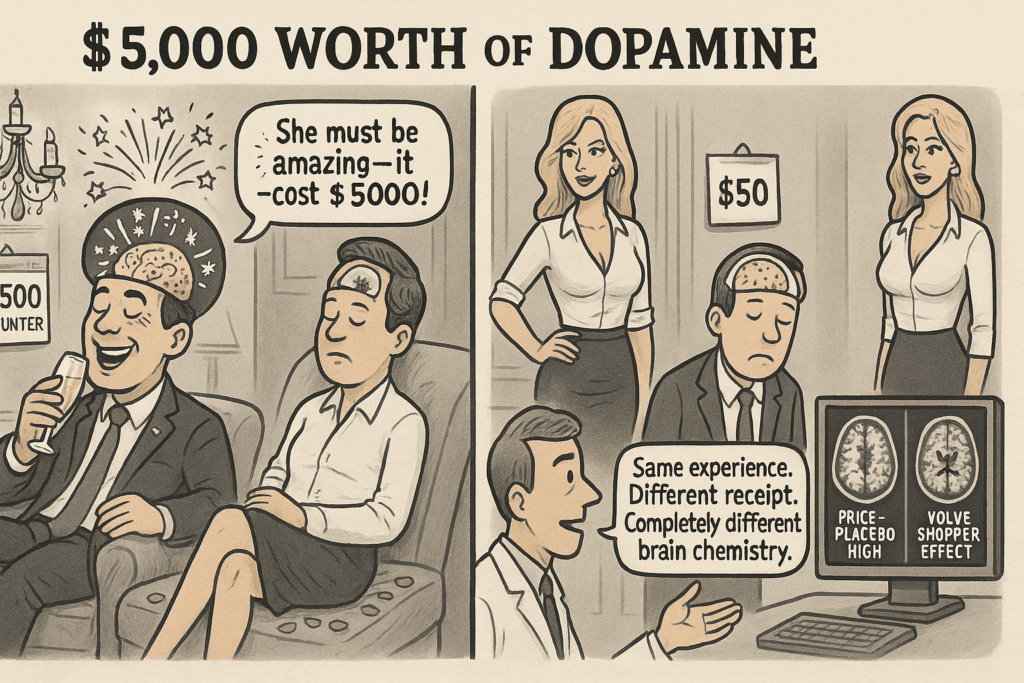

Brain scans revealed that people didn’t just say the “expensive” wine tasted better—their pleasure centers lit up like Times Square on New Year’s Eve. The wine literally tasted better to them because they believed it cost more. Their neurons were having a party, and the price tag was the DJ.

The Spitzer Situation: A $10,000 Case Study

Which brings us to the elephant in the hotel room: Eliot Spitzer and his infamous $10,000 liaisons. Now, I’m not here to judge the former governor’s extracurricular activities (that’s what Twitter is for), but from a psychological perspective, his scandal offers a fascinating glimpse into how the price-placebo effect operates in, shall we say, more intimate settings.

Consider the math: $10,000 for an evening’s companionship. That’s roughly the cost of a decent used car, a year’s worth of avocado toast, or 200 sessions with an actual therapist. But here’s the kicker—was the experience really 20 times better than a $500 encounter? Or 200 times better than a $50 one?

If we hooked up Spitzer’s brain to those same scanners (and wouldn’t that have made for interesting headlines), we’d likely see his pleasure centers going absolutely bonkers. Not necessarily because the service was objectively superior, but because his brain was convinced it must be—after all, he paid ten grand for it.

Your Brain: The Ultimate Con Artist

The price-placebo effect is essentially your brain running a con game on itself. It works through two psychological mechanisms that are as powerful as they are ridiculous:

1. Expectation Inflation: When you pay more for something, your brain expects it to be better. And like a self-fulfilling prophecy written by a particularly cynical fortune teller, it often is—in your perception, at least. Your neurons essentially whisper, “This costs a fortune, so it must be fantastic,” and then proceed to make it so.

2. Cognitive Dissonance Reduction: Nobody wants to feel like a sucker. So when you’ve dropped serious cash on something, your brain goes into overdrive to justify the expense. It’s like having a tiny lawyer in your head, desperately building a case for why that $10,000 experience was totally worth it. “Your honor, my client’s pleasure centers clearly indicate extraordinary satisfaction!”

The Neuroscience of Nonsense

Here’s where it gets properly weird. When those Caltech researchers scanned people’s brains while they drank the “expensive” wine, they found increased activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex—the brain’s pleasure headquarters. This wasn’t just people being polite or trying to seem sophisticated. Their brains were literally experiencing more pleasure.

It’s as if your neurons have a price detector that automatically adjusts your enjoyment levels. “Oh, this costs $200? Better crank up the happiness hormones!” It’s simultaneously amazing and slightly depressing that our brains can be so easily bamboozled by a number on a price tag.

Real-World Ridiculousness

The price-placebo effect isn’t limited to wine and questionable life choices. It’s everywhere:

Medication: Studies show that patients experience better pain relief from expensive pills than cheap ones—even when they’re identical. Pharmaceutical companies must love this.

Fashion: That $2,000 handbag doesn’t just carry your stuff; it carries the weight of its price tag, making you feel more confident and stylish. The $50 knockoff? Your brain knows, and it judges you accordingly.

Restaurants: The $200 tasting menu at that Michelin-starred restaurant? Your brain is primed to find every bite transcendent. The same chef could serve you the same food at a food truck, and your neurons would shrug with indifference.

Education: Parents convinced that expensive private schools are inherently better might actually see better results—not because the education is superior, but because everyone involved expects it to be.

The Million-Dollar Question (Marked Down from Ten Million)

So where does this leave us? Should we all start overpaying for everything in the hopes of tricking our brains into maximum enjoyment? Should restaurants add a “placebo surcharge” to enhance our dining experience?

The answer lies in understanding the effect without becoming its victim. Yes, paying more can genuinely increase your subjective enjoyment—those brain scans don’t lie. But knowing about the effect gives you power over it. You can choose when to indulge in the illusion and when to see through it.

The Sweet Spot of Self-Deception

Here’s the thing about the price-placebo effect: it’s not entirely bad. If spending more money actually increases your enjoyment, and you can afford it, who’s to say that’s wrong? It’s like a magic trick where you’re both the magician and the audience, and everybody wins.

The key is balance. Save the expensive experiences for special occasions when the placebo boost is worth the cost. But don’t let marketers manipulate your neurons into bankruptcy. Your brain might be easily fooled, but your bank account keeps better records.

The Spitzer Postscript

As for our friend Eliot and his $10,000 adventures? Whether he got his money’s worth depends entirely on which part of his anatomy you’re asking. His pleasure centers probably gave it five stars. His career, somewhat less enthusiastic reviews.

The real lesson isn’t about the morality of his choices (again, that’s Twitter’s job), but about the powerful ways price influences our experience. Whether it’s wine, companionship, or anything in between, our brains are wired to conflate cost with quality.

The Bottom Line (Expensively Underlined)

The price-placebo effect reveals a fundamental truth about human psychology: we’re not nearly as rational as we think we are. Our brains are constantly playing tricks on us, using price as a shortcut to determine value and enjoyment.

But here’s the beautiful irony—knowing about the effect doesn’t necessarily diminish it. You can read this entire article, understand the science completely, and still get extra enjoyment from that overpriced wine tonight. Your conscious mind might know it’s a trick, but your pleasure centers don’t care about your intellectual insights.

So the next time you’re debating whether to splurge on the expensive option, remember: you’re not just buying a product or service. You’re buying a neurological experience, complete with enhanced pleasure receptors and satisfaction guarantees written in neurotransmitters.

Whether that’s worth $10,000 is between you, your brain, and your accountant. But at least now you know why your neurons are so easily impressed by a price tag. They’re not shallow—they’re just wired that way.

And if you think this article was particularly insightful, well, that might be because I’m charging $500 to read it. (Just kidding—but wouldn’t it be better if I weren’t?)

The author promises that no neurons were harmed in the writing of this article, though several synapses did experience mild financial anxiety.